Logo of Love - No Harp, No Story?

Article by Louisa John-Krol 7th June 2016

This piece is part of a History series for our storytelling community, which overlaps with our faerie realm. There are, naturally, areas where no such cohabitation occurs. My fey blog is a point where those circles touch. Perhaps even glinder, glimmer and gleam. Ok, I made up the word 'glinder'. We can never have too many verbs. Especially in stories!

Post-beam editing is possible, so you're welcome to notify me of oversights. I'm grateful for contributions so far.

Forthcoming articles include an exploration of how Victoria's first Storytelling Guild came to be, with focus on co-founder Nell Bell. For now, you can read a report on our visit to Nell, in an earlier post here.

|

| Design by illustrator David Wong |

|

| David Wong, illustrator |

Next, along came green badges featuring a map of Australia with gold border. Monty and Nell designed the badge, pictured below:

|

| Original Badge of The Storytelling Guild of Australia (Victoria) |

|

| Original Banner of The Storytelling Guild of Australia (Victoria) |

Below centre: resulting quilted colour banner, still in use today, 2016.

|

| Storyteller Susan Pepper |

|

| Storytelling Victoria banner, still in use 2016 |

At first glance, our logo seems to herald Celtic lore. Partly true. “After all”, writes Californian storyteller-harpist Patrick Ball, “Celtic harp has always been used to accompany the telling of Irish tales. Tall tales, tales of little people and hard lands, stories of love and loneliness - these reflect the Celtic soul”; Patrick has released albums of stories with harp music since 1983 on Celestial Harmonies / Fortuna Records.

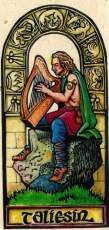

There is a Welsh flood story of the village Ys on Alan Stivell’s album Renaissance of the Celtic Harp, an influence upon Canadian singer-harpist Loreena McKennitt (evoking Pre-Raphaelite poems); also upon Andreas Vollenweider, a multi-instrumentalist. Early Welsh poet Taliesin was depicted playing harp, and some associate him with Ceridwen’s cauldron of inspiration, and with The Mabinogion, the earliest prose literature of Britain. Scholars suggest there were probably two Taliesins; the first dating back to the 6th century; the second chronicled in medieval manuscripts.

There is a Welsh flood story of the village Ys on Alan Stivell’s album Renaissance of the Celtic Harp, an influence upon Canadian singer-harpist Loreena McKennitt (evoking Pre-Raphaelite poems); also upon Andreas Vollenweider, a multi-instrumentalist. Early Welsh poet Taliesin was depicted playing harp, and some associate him with Ceridwen’s cauldron of inspiration, and with The Mabinogion, the earliest prose literature of Britain. Scholars suggest there were probably two Taliesins; the first dating back to the 6th century; the second chronicled in medieval manuscripts.The Irish harp Uaithne belonged to the Dagda, an important god in Irish mythology: a protector of the people. His magical harp played itself! One of the most revered of these harpists was Turlough O'Carolan, who was blind. Born in Ireland in the 18th century, he was also a composer and singer. Harps were burned and harpists executed, as travelling harpists were thought to stir rebellion amongst the Irish people. Such music often accompanied bards reciting poetry. The Celtic Triangular Harp was known as the instrument of the Bards. Naturally, the bardic harp was as much a part of Scottish culture as it was of Irish and Welsh.

The harp is a multi-stringed instrument. Its strings are made from a variety of materials including wire, silk, nylon or gut. Their plane is positioned perpendicularly to the soundboard. Although in the category of Chordophones (as are all stringed) the harp has its own sub category, Harps. All harps are made up of a neck, resonator and strings. Frame harps also have a pillar. Harps without a pillar are known as open harps. Smaller harps can be played in a lap, but more often stand while the harpist sits beside it. Most popular in Ireland is the folk harp.

Yet the logo also alludes to the Greek Lyre of Orpheus, revered bard of classical antiquity, for example in the legend of Jason and the Argonauts. Centuries later, he reappeared in the medieval romance Sir Orfeo, garnering longevity of troubadours, of Italian fairy tales and French salons.

The image below, courtesy of Mark Cartwright, Encyclopaedia of Ancient Art, portrays a lyre that resembles a harp.

Yet the logo also alludes to the Greek Lyre of Orpheus, revered bard of classical antiquity, for example in the legend of Jason and the Argonauts. Centuries later, he reappeared in the medieval romance Sir Orfeo, garnering longevity of troubadours, of Italian fairy tales and French salons.

The image below, courtesy of Mark Cartwright, Encyclopaedia of Ancient Art, portrays a lyre that resembles a harp.

|

| Ancient lyre |

|

| Daemonia Nymphe instrument: barbitos |

A modern Greek ethereal world band, Daemonia Nymphe, established by Spyros Giasafakis and Evi Stergiou, currently based in England, has revived ancient instruments from their heritage, such as lyre, barbitos and pandoura (from the lute family), constructed by Nicholas Brass with authentic materials of antiquity, often accompanied by recitals from odes, Orphic or Homeric hymns, and Sappho’s poems for Zeus and Hekate. Their theatrical shows feature masks and robes of their own design. Other harps in ancient Greece included the trigonon and piktis.

By the Renaissance, the most popular instrument in the Western world was not harp or lyre. It was the lute. Still the legacy of linking music to words continued, not only in the courts, streets and alehouses, but in playhouses, providing accompaniment to Elizabethan plays. Later, studio recording rekindled that marriage of music and word, e.g. “Shakespeare Songs” by the Deller Consort (1967) on Harmonia Mundi.

A Dutch Harp festival (DHF) in 2014 carried the theme No Harp, No Story, “a direct reference to the harpist’s original function as a teller of tales and gatherer of news”. No Harp, No Story is at the website of Remi Vankesteren.

|

| Remi Vankesteren |

For thousands of years, the harp has been the instrument of storytellers, from ancient Egypt to our medieval troubadours and minstrels.

|

| Toumani Diabaté |

|

| Kora - ref: Kaypacha |

Metaphorically, our instrument might just as well be a fiddle, didgeridu or drum. A reed in the hands of a Pied Piper. It need not even imply accompaniment. It is a directive, a symbol of power, a tool that casts a spell like a wand or staff; or sends a signal: “my turn to speak”, as in tribes that pass around the speaker’s rod.

In Australian indigenous culture, music and storytelling are deeply entwined in imparting ceremonial (or other) traditions. Most Aboriginal instruments are in the idiophone class, wherein instruments consist of two parts joined to form a percussive sound. Throughout the continent, this takes many forms, including membraphones (skin drum types). There are no chordophones or stringed instruments, though there are aerophones (wind instruments). Regardless of physical form, the purpose of Aboriginal music is to keep culture alive. In this, words are paramount.

Indeed, language itself can be musical. An instrument is a reminder, a key. Could this be the meaning of the phrase “No harp, no story”?

The Harp that Once Through Tara’s Halls

Thomas Moore

(1779–1852)

The Harp that once through Tara’s halls

The soul of music shed,

Now hangs as mute on Tara’s walls

As if that soul were fled. So sleeps the pride of former days,

So glory’s thrill is o’er,

And hearts, that once beat high for praise,

Now feel that pulse no more.

No more to chiefs and ladies bright

The harp of Tara swells:

The chord alone, that breaks at night,

Its tale of ruin tells. Thus Freedom now so seldom wakes,

The only throb she gives,

Is when some heart indignant breaks,

To show that still she lives.